artists in residence

artists in residence Lijiang and Shangri-la, China

text by gregory burns

photos by angie tan

Climbing the two flights of steep, wheelchair inaccessible stairs up into the bowels of the China Embassy in Singapore to retrieve Angie and my passports with visas, I am reminded of the challenges that lie ahead as we prepare to reenter the Center Kingdom. With a growing number of disabled people equal to the entire population of Thailand, one might think that China would understand the need for accessibility. But then again, this would be China….

TG 612 brings us into Kunming as we enter the backside of the country. Yunnan opened her doors to me almost a decade ago when traveling with fellow artists from Singapore. Now I return with a determination to paint a modern version of this ancient land. Yet, I have little idea of what will transpire. I can only trust that my previous sense of this place will combine with some contemporary view to produce something beyond the surface of clay tiled roofs and stone bridges. We travel like rock stars on tour, looting locations of inspiration in order to feed the urge to create and once again recreate something memorable while passing through. As we glide into the old part of a new China, we disembark with few clues as to what will happen but filled with anticipation and promise. So far, the ride has been smooth. But then again, we haven’t crossed the border yet.

TG 612 brings us into Kunming as we enter the backside of the country. Yunnan opened her doors to me almost a decade ago when traveling with fellow artists from Singapore. Now I return with a determination to paint a modern version of this ancient land. Yet, I have little idea of what will transpire. I can only trust that my previous sense of this place will combine with some contemporary view to produce something beyond the surface of clay tiled roofs and stone bridges. We travel like rock stars on tour, looting locations of inspiration in order to feed the urge to create and once again recreate something memorable while passing through. As we glide into the old part of a new China, we disembark with few clues as to what will happen but filled with anticipation and promise. So far, the ride has been smooth. But then again, we haven’t crossed the border yet. But then this is China and the calm was soon to change. Clearing customs without a hitch I am then reacquainted with amongst other things, the spitting and smoking, which take place in the toilets. We whisk through baggage claim and up the elevator to check in to our China Eastern flight to Lijiang. The cavernous Kunming airport is filled with stands and stalls selling everything from tea to sunflower seeds. The sign above line 22 indicates that this is where ‘disabled passengers’ without baggage check-in. After the handicapped friendly elevator and bathrooms in the arrival hall, I am impressed with the accessibility of this new China. But my enthusiasm for open-mindedness soon fades. We are informed that the baggage allowance is only 20kg per person and we are over by 24kgs. So we must pay over weight fees in Yuan (local cash currency), which we have none of. And the market of an airport sells everything but cash. The ATM machines reject my cards. Nobody will change US$ or Singapore Dollars for Chinese currency. This seems crazy as just a decade ago swarms of locals would accost any foreigner tourist and ask them to ‘change money?’ But not in today’s China.

But then this is China and the calm was soon to change. Clearing customs without a hitch I am then reacquainted with amongst other things, the spitting and smoking, which take place in the toilets. We whisk through baggage claim and up the elevator to check in to our China Eastern flight to Lijiang. The cavernous Kunming airport is filled with stands and stalls selling everything from tea to sunflower seeds. The sign above line 22 indicates that this is where ‘disabled passengers’ without baggage check-in. After the handicapped friendly elevator and bathrooms in the arrival hall, I am impressed with the accessibility of this new China. But my enthusiasm for open-mindedness soon fades. We are informed that the baggage allowance is only 20kg per person and we are over by 24kgs. So we must pay over weight fees in Yuan (local cash currency), which we have none of. And the market of an airport sells everything but cash. The ATM machines reject my cards. Nobody will change US$ or Singapore Dollars for Chinese currency. This seems crazy as just a decade ago swarms of locals would accost any foreigner tourist and ask them to ‘change money?’ But not in today’s China.Our flight and our bags leave in 20mins. I race around the airport pleading with strangers to change money. Finally in desperation we return to the airline counter and explain that my clean crisp US$20 bill would equal the fee we need to pay. They call a supervisor to get an okay for this high finance while the clock is ticking away. Finally, exasperated, the crew that has assembled waves us on and doesn't even take our cash. Thus ends what we consider a rather pathetic moment in airline history but we are on our way. Or at least we think we are. The security line is packed with hundreds of locals with bags of bags. I see a VIP counter and duck in. Surprisingly, they let us in and we put our bags on the conveyer belt. We go through and are ready to race to the plane, which leaves in 3 minutes when the security guard decides to take me into a private room for a near strip search. He rolls up my pants legs and bangs on my braces, looking for Bin Laden. We are about to leave when he questions our 2 bottles of red wine. I am about to explode when suddenly the planets align and he waves us on. We are the last ones to board and the plane doors close behind us. Welcome to the Kingdom.

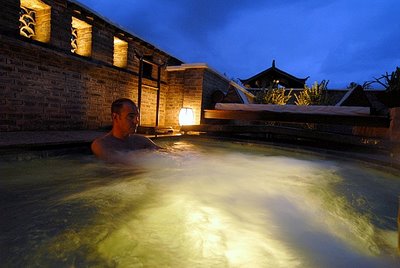

And just like all travel, the opposites switch places and the sunshine returns. In Lijiang we are whisked away to the Banyan Tree where the nightly turn down service is much more than a bedside chocolate. Here, we will photograph and paint for the next three weeks before doing the same at Banyan Tree Ringha in Tibet. This oasis reminds us that our travels are always filled with both Yin and Yang and getting attached to either is pointless.

And just like all travel, the opposites switch places and the sunshine returns. In Lijiang we are whisked away to the Banyan Tree where the nightly turn down service is much more than a bedside chocolate. Here, we will photograph and paint for the next three weeks before doing the same at Banyan Tree Ringha in Tibet. This oasis reminds us that our travels are always filled with both Yin and Yang and getting attached to either is pointless.

This is Angie’s first trip to Yunnan and Tibet. She clicks away several hundred shots a day featuring old buildings, local folks, means of conveyance and the natural setting that surrounds this valley ringed by steep mountain peaks. We spend several days between painting sessions wandering the old towns and mountain areas.

Joining a fellow photographer Felix and his producer Jamie, we take the cable car to 4,600 meters and into the snowy mountains and craggy glaciers. Struck by the beauty and the amount of Chinese tourists we soon realize that we will never understand the priorities of those who seem to travel to distant places hell-bent on having their pictures taken in some angelic pose. I sketch and the others snap pictures before we descend and head to the market square. Our local meal comes complete with wandering minstrels singing Chinese rock into portable amplifiers that clear the outdoor eatery of customers while we tuck into our first course.

Joining a fellow photographer Felix and his producer Jamie, we take the cable car to 4,600 meters and into the snowy mountains and craggy glaciers. Struck by the beauty and the amount of Chinese tourists we soon realize that we will never understand the priorities of those who seem to travel to distant places hell-bent on having their pictures taken in some angelic pose. I sketch and the others snap pictures before we descend and head to the market square. Our local meal comes complete with wandering minstrels singing Chinese rock into portable amplifiers that clear the outdoor eatery of customers while we tuck into our first course.

The town of Lijiang has morphed since I was here a decade ago. Now, shops selling tourist trinkets flank all the narrow stone streets and alleys. I prefer my memory but realize that China has not sat still and the whole country is racing head first into consumerism and capitalism.

After a week of languishing in the old and new towns with my mixed feelings about combining the ancient and the contemporary, I finally make a minor break through on day 14. I have managed to merge imagery of the crusty old with bold strokes of the vibrant new in a soup of local reds and mauves. I realize that it takes time being in a place before we can internalize all that lies below the surface. The rhythmic patterns of the tiled roofs juxtaposed with the rippling streams that meander through the towns and provide life to the inhabitants have become part of me. The massive mountains that ring this bountiful valley which once kept out strangers no longer bar entry. Foreigners venture from afar and make up less than one percent of the patrons at the KFC outside the old town gate. But the majority of tourists hail from inside the Center Kingdom and have a passion for travel and sightseeing that will consume the world.

How can we forget the saying and the image of the 'starving artist'? We envision Van Gogh struggling with his canvas and Beethoven at war with his notes. Behind these scenarios is the understanding that they, like other artists, lived troubled lives. Whether poor or tormented, suffering health problems or battling society and circumstances, it seems the artist is meant to struggle. If not on the outside then all the more on the inside.

It is a stretch to intimate that we are in any way struggling here at this five-star resort where room service and housekeeping provide for our needs. Yet, in my art and in Angie’s photos, there must be some challenge. And if there seems to be no external friction to feed the work, then one can be sure that an internal dialogue is raging; where the outcome and concept never seem to connect or the feeling can not be made concrete. As artists, we do starve, we run out of energy and inspiration. We must constantly wake ourselves from our slumber and complacency to keep pushing beyond what has been done before.

A decade ago when I painted Lijiang, I felt an immediacy and passion that fueled my paintings. Today, it is different. There is time and distance from that place and person I was a decade ago and it is fruitless to attempt a retreat to things that once worked. If we are to progress and make anything of merit, we must continue to search the obscure landscapes in our lives for that new spark which can again ignite a passion for creation and our place in it. Pushing forward from this point of wonder, we continue on our journey as artists. All this makes me hungry; and I wonder if the in-room-dining menu is beside the jacuzzi?

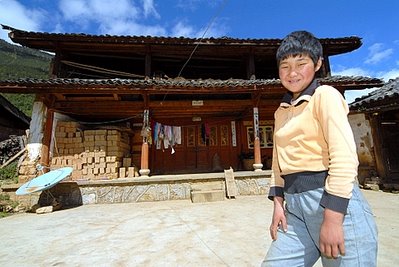

An hour of bumpy driving by jeep from the Banyan Tree is the village of Wen Hai. The road, constructed just recently is paved for the first 10%. After that we are on our own and climb high above Lijiang. Tucked into a mountain fringed valley, we are staring the clouds in the face as they sputter and flutter over the nearby peaks. This hamlet of eleven families we are told has seen little of the outside world. The architecture though similar to that of Su Hu and Bai Sa, the feeling here is more quiet.

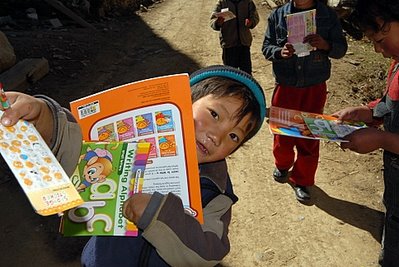

Remote as it is, there is still a TV dish in the courtyard of the first home we stop in front of. At first, it seems that the village is deserted. It is silent except the sound of the wind in the trees. Then slowly as I draw and Angie takes pictures, children emerge. Old ladies with baskets on their backs walk past. A dog comes out of the shadows. Soon, we are in the middle of village life and communicating with the locals. Angie snaps away and I draw the homes from which these people have surfaced. There is the 63 year old grandmother of the 12 year old who only says “I don’t know” and who is not the boyfriend of the 13 year old who carries a child on her back.

After a few hours we take our leave but not before trying unsuccessfully to share our picnic lunch with some reluctant connoisseurs.

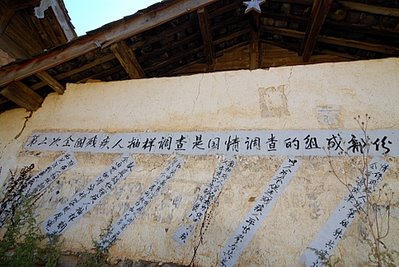

After a few hours we take our leave but not before trying unsuccessfully to share our picnic lunch with some reluctant connoisseurs. Driving back out of the village, we see a building with some banners. Angie reads that they are announcing a survey for local disabled people and the message seems to be encouraging for the disabled. Even here in this small village we see a wheelchair. Back in Lijiang we notice special bumpy tiles on the pavement which allow the blind to navigate city streets. The handicapped are also exempt from the entry fees to parks and tourist sites. I am beginning to think that China has not only progressed with its tourism industry, but with disability awareness as well.

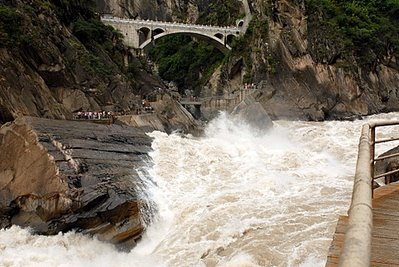

Driving back out of the village, we see a building with some banners. Angie reads that they are announcing a survey for local disabled people and the message seems to be encouraging for the disabled. Even here in this small village we see a wheelchair. Back in Lijiang we notice special bumpy tiles on the pavement which allow the blind to navigate city streets. The handicapped are also exempt from the entry fees to parks and tourist sites. I am beginning to think that China has not only progressed with its tourism industry, but with disability awareness as well.Leaving Lijiang again, we travel to Tiger Leaping Gorge, which resembles a parking lot at Wal-Mart, on our way to the Banyan Tree Ringha.

Climbing to 3,300 meters above sea level we soon leave behind much of the clutter of China. We enter a quiet kingdom on the fringes of the Center Kingdom.

Climbing to 3,300 meters above sea level we soon leave behind much of the clutter of China. We enter a quiet kingdom on the fringes of the Center Kingdom.

Far from any town, down a potted mud road, past fields and over streams, we feel removed. The remoteness is pleasing and we easily slide into the calming dusk. We have arrived, half way through our journey, in Shangri-la. The villages surrounding the Resort are dotted with stockade type homes, built of local materials. The structures, mostly two-stories taper towards the top with roofs made of wooden planks. No more tiles. The orange-green valley is pock-marked with black and white yaks. The sun cuts almost horizontal in the late afternoon, lending a crisp light to all it touches.

Far from any town, down a potted mud road, past fields and over streams, we feel removed. The remoteness is pleasing and we easily slide into the calming dusk. We have arrived, half way through our journey, in Shangri-la. The villages surrounding the Resort are dotted with stockade type homes, built of local materials. The structures, mostly two-stories taper towards the top with roofs made of wooden planks. No more tiles. The orange-green valley is pock-marked with black and white yaks. The sun cuts almost horizontal in the late afternoon, lending a crisp light to all it touches.  The sky, so vast and strewn with clouds of multiple colors and forms, as significant as the landscape below. Stupas and prayer flags signal the presence of Buddhists and the peace is warming.

The sky, so vast and strewn with clouds of multiple colors and forms, as significant as the landscape below. Stupas and prayer flags signal the presence of Buddhists and the peace is warming.Early on our third morning we walked up to Da Bao Monastery on the nearby hill and spent half the day just being there.

Angie taking pictures and me sketching. The old man caretaker showed us around. The monk came out of his hovel and chanted. The goats kept the pigs out of the courtyard as the chickens crowed for all to rise and look inside.

Angie taking pictures and me sketching. The old man caretaker showed us around. The monk came out of his hovel and chanted. The goats kept the pigs out of the courtyard as the chickens crowed for all to rise and look inside.

The forest around the complex is layered with prayer flags, fluttering blue, red, green and yellow in the wind- taking sentiments to heaven. The sky turned blue today as the clouds finally decided to roll away. The light is crisp as we wander through the village of Tibetan homes. Like the light, the homes resemble Swiss chalets in the mountains except for the yaks that live on the ground floor. We step down a gear and begin to recall what the locals already know- that being content is the way to go.

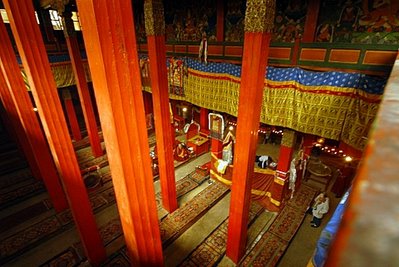

The forest around the complex is layered with prayer flags, fluttering blue, red, green and yellow in the wind- taking sentiments to heaven. The sky turned blue today as the clouds finally decided to roll away. The light is crisp as we wander through the village of Tibetan homes. Like the light, the homes resemble Swiss chalets in the mountains except for the yaks that live on the ground floor. We step down a gear and begin to recall what the locals already know- that being content is the way to go.Heralded as the minor cousin of the Potola Palace in Lhasa, Songzanlin Monastery rests on the side of a hill outside the town of Zhongdian. Monks and tourists roam the courtyards and halls, seeking visions.

The wall murals, sculptures and Tonka paintings offer clues into a religion shrouded in burgundy robes. Prominently displayed throughout the temples and alcoves are photos of the Beijing installed Lama meant to replace the Dalai Lama in the hearts of the Tibetans. Behind a secondary alter I found one dusty photo of his Holiness, set next to a shiny portrait of the 'imported’ Lama. In the hall outside for sale one can find images of the ‘new’ Lama with what appear to be beams of light emanating from his head.

The wall murals, sculptures and Tonka paintings offer clues into a religion shrouded in burgundy robes. Prominently displayed throughout the temples and alcoves are photos of the Beijing installed Lama meant to replace the Dalai Lama in the hearts of the Tibetans. Behind a secondary alter I found one dusty photo of his Holiness, set next to a shiny portrait of the 'imported’ Lama. In the hall outside for sale one can find images of the ‘new’ Lama with what appear to be beams of light emanating from his head.

Though the structures and trappings are authentic, I do not sense the same religious fervor that I experienced in Lhasa or even in the little Da Bao Monastery.

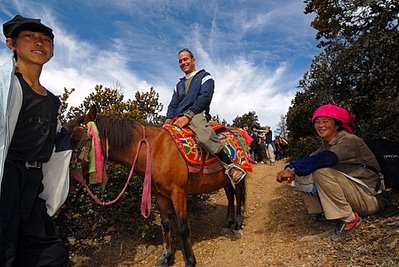

Though the structures and trappings are authentic, I do not sense the same religious fervor that I experienced in Lhasa or even in the little Da Bao Monastery.Angie finally managed to extract me from my makeshift studio below our villa and we traveled by foot and horse to visit the nomads who live high in the mountains behind the Banyan Tree Resort.

Along with a German TV crew and a team of local Tibetans, we ventured into the beautiful landscape of deep orange, reds and multiple greens. After a few hours we reached the high meadow where the nomads live during the summer with their yaks.

Along with a German TV crew and a team of local Tibetans, we ventured into the beautiful landscape of deep orange, reds and multiple greens. After a few hours we reached the high meadow where the nomads live during the summer with their yaks.

A lonely existence, these hardy folk survive on yak butter, grains and fresh air and seem content. After some filming and lunch we descended by a different route. The trail doubles as a logging track where yaks drag denuded trees out of the mountains and down to the villages. While only Tibetans are allowed to log, these huge trees become homes someday and parents give them to their children as a kind of dowry. One of the best parts of the whole adventure was the opportunity to interact with the locals and to begin to understand their lives.

A lonely existence, these hardy folk survive on yak butter, grains and fresh air and seem content. After some filming and lunch we descended by a different route. The trail doubles as a logging track where yaks drag denuded trees out of the mountains and down to the villages. While only Tibetans are allowed to log, these huge trees become homes someday and parents give them to their children as a kind of dowry. One of the best parts of the whole adventure was the opportunity to interact with the locals and to begin to understand their lives.I watched in awe how seven small men managed to bundle logs 5 meters in length and almost a meter thick, into an open sided truck.

They first constructed a ramp system to roll the timber downhill before man-handling it the remaining distance up a makeshift ramp and onto the growing pile of logs. At any moment, a man could loose a hand, leg or life were one of the unwieldy trees to get loose. From a distance, I understood that a man without the use of his legs in this environment would be severely hindered and would need to find something to do in order to offset his inability to fell trees or corral yaks. Perhaps this is why when passing by, the locals look at me with saddened faces. In their world, a handicap means game over.

They first constructed a ramp system to roll the timber downhill before man-handling it the remaining distance up a makeshift ramp and onto the growing pile of logs. At any moment, a man could loose a hand, leg or life were one of the unwieldy trees to get loose. From a distance, I understood that a man without the use of his legs in this environment would be severely hindered and would need to find something to do in order to offset his inability to fell trees or corral yaks. Perhaps this is why when passing by, the locals look at me with saddened faces. In their world, a handicap means game over. Our last adventure included a long day's bumpy drive to and from Mei Li Snow Mountain, a towering mass of rock and snow along the road to Lhasa.

The Gods smiled upon us, allowing for a clear view of the usually cloud shrouded peaks. Along this 'road in progres' we watched teenagers spreading basket-loads of dirt and rubble onto the surface of the gravel road. Traveling overland in China is never easy, but making roads is no picnic.

The Gods smiled upon us, allowing for a clear view of the usually cloud shrouded peaks. Along this 'road in progres' we watched teenagers spreading basket-loads of dirt and rubble onto the surface of the gravel road. Traveling overland in China is never easy, but making roads is no picnic.

They do what they have done for centuries. Long after our buildings and machines have gone, these folks will still be up everyday at dawn to milk their yaks. There is a constancy here that settles the soul and reminds us of the magnificence found in the little things in life.

They do what they have done for centuries. Long after our buildings and machines have gone, these folks will still be up everyday at dawn to milk their yaks. There is a constancy here that settles the soul and reminds us of the magnificence found in the little things in life.